Tax included, Shipping not included

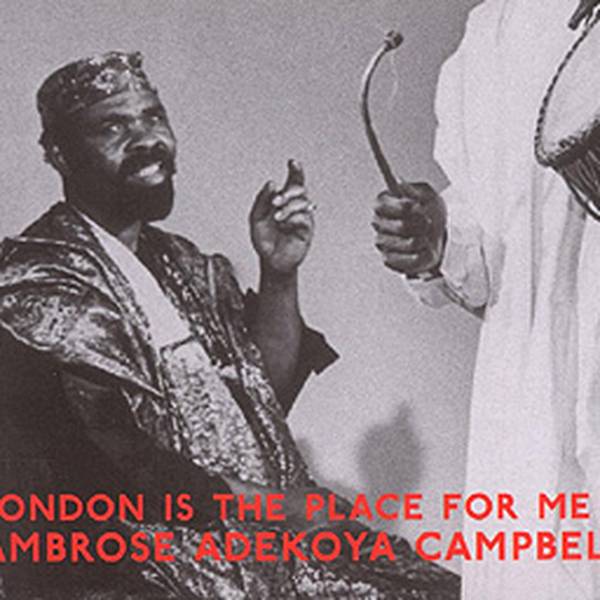

Television has given us a picture of the day in 1945 war ended in Europe. Nostalgic black-and-white film footage captured the celebrations as men and women danced in the Trafalgar Square fountains and embraced complete strangers. You can almost smell the Woodbines and brown ale. Caught up in that VE Day throng — although not recorded on film — was a band of Nigerians carrying drums and guitars. A little bruised and battered maybe — and far, far wiser than when they left their West African homes to go to sea — they had learnt survival ways in a war-torn Blighty and wanted to add their own voice.

As blackout curtains were torn down from windows everywhere, the Nigerians made their way to Piccadilly Circus and joined in. For Ambrose Campbell and his friends, VE Day marked the public debut of a group — to be known by many names including the West African Rhythm Brothers — that would go on to become an ubiquitous presence in London musical circles. But it was more. For these time-serving veterans of difficult times, the event was another step in a journey to becoming what they themselves called 'Englishmen'.

A newspaper reporter, remarking on their presence, called them 'West Indians'. The mistake was probably inevitable at the time, given the prevailing ignorance about 'foreigners', not to mention the presence in Britain of a visible contingent of Caribbean servicemen. But the stokers and trimmers of the merchant navy were often from Africa, and among the people who helped keep many a wartime convoy afloat.

Born in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1919, Ambrose Campbell grew up in a strict Victorian household with a preacher father who educated his children in the family compound. His Yoruba name was Oladipupo Adekoya, and as a youngster he sang in his father's church choir. When the Rev. Campbell embarked on evangelizing missions, his son's dulcet tones were employed for attracting the public. He found excitement at night by sneaking out to where palm-wine was sold: stalls under the moonlight where seamen and servants gathered to sing and play music, and drink the sweet, cloudy beverage. Coming from places as far away as Liberia, Guinee and Cameroun, these men carried with them diverse cultural traditions. They also brought Western ideas picked up on their travels. Influences were exchanged and combined as they played. When he was old enough, Campbell joined them, singing and beating a tambourine.

With a group of young friends, he entertained at Christmas events; but war was looming, and soon Campbell was himself on the high seas, below decks and headed for Britain. He spent a few days in Liverpool before returning to Lagos; on a second visit, though, he jumped ship and headed for the capital. Hardship ensued in the grim days of the war, but it wasn't all misery. Casual racism abounded but friends emerged too — English people who appreciated the vitality of the newcomers — and amidst the bombing, a small group of Africans would meet up to play guitar and drums, between pints of Guinness and bitter.

After the deprivations of war, people everywhere were hungry for novelty and change. 1946 saw the emergence of Britain's first black ballet company, Les Ballets Negres, and Nigerian musicians headed by Ambrose Campbell accompanied the dancers on the London stage. For the occasion, two newcomers arrived from Manchester: bongoes-player Ade Bashorun (from Lagos, the only professional musician in the group) and Brewster Hughes, from Ibadan in Western Nigeria, a teacher by occupation and a brilliant guitarist. A British tour and a spell in Paris followed the London debut of the Ballets.

Campbell's affable personality and the quality of his voice dictated that he should be leader. At first he sang mainly, and played percussion; though he had always dabbled on guitar, he did not start learning the instrument seriously until he took lessons from the Trinidadian Lauderic Caton. This association with a Caribbean musician was unusual, but multiplied when Campbell added two newly-arrived Barbadians to the mix (Harry Beckett on trumpet, Willy Roachford reeds) and his innovations continued when he brought in a schooled pianist, Adam Fiberesima (equally unusually an Ijo, from the East of Nigeria).

Around 1952, the West African Rhythm Brothers found a permanent showcase as residents at the Abalabi in Soho's Berwick Street market. A nightclub opened by Ola Dosunmu and run by him and his English wife, this became one of the most famous clubs of the era and a magnet for a wide cross-section of humanity. Afro-Cuban rhythms were popular at the time, and Dizzy Gillespie's experiments with Chano Pozo — a Cuban drummer from the Yoruba lucumi cult — had penetrated the London jazz consciousness. Accordingly, jazz musicians came to the Abalabi to hear the 'real thing'. Others came to dance the highlife, the new West African dance which combined traditional rhythms with Western jazz and swing voicings and harmonies. Long after the market stalls closed down for the night, Nigerian students and dignitaries joined ex-colonials to dance to the new beat, while debs and other high-flyers made themselves at home in the funky basement, rubbing shoulders with the hustlers, gamblers and hookers of Soho.

All this took place at a time when London was still riddled with bomb-sites. The winters were cold, with snow that settled, and traffic regularly ground to a standstill in the fog. Rationing was still in place and clothes were drab. In this post-war scene, the Nigerians grappled with the realities of sensory deprivation and coal fires, finding substitutes for familiar food until rare moments when seamen brought a memory of home.

Importantly, Ambrose Campbell was beloved by London's jazz community. Musicians went to the Abalabi and Club Afrique — its successor — to learn at the source. Saxophonists Tubby Hayes and Ronnie Scott studied there whilst carousing. 'Ambrose was a bit special,' Scott told me years ago, 'a bit of a musicologist.' Kenny Graham, who led his own Afro-Cubists and employed several African percussionists, was a regular. And Phil Seamen — the most African of English drummers — was Campbell's number one fan, passing on what he learnt.

Just as Ambrose knew everyone who was anyone, his own importance as a cultural figure was recognised by an astonishing range of people, from the playwright George Bernard Shaw to Prince Buster. Shaw was among the notables who sponsored Les Ballets Negres: although famously vegetarian himself, he allegedly had chicken cooked for the band. And when Buster was photographed for the sleeve of his Melodisc collection I Feel The Spirit, it was Ambrose who lent him a talking-drum and agbada.

Ambrose is part of the story of Soho in the 1950s – but, apart from his good friend Colin MacInnes (who includes him as Cranium Cuthbertson in his somewhat sensationalist City Of Spades), few chroniclers give him house-room in surveys of the Bohemian quarter. It's a shocking omission, especially given the fame of the Abalabi in its day. When Dosunmu moved his operation to the more up-market Club Afrique in Wardour Street, Campbell formed another new band to play there. He alternated with Brewster Hughes' Starlite Tempos — the pair feuded and periodically went separate ways – while the venture continued into the 1960s. Fire-eating was staged there occasionally, and a temporary switch to Caribbean bands was attempted before the Dosunmus relocated to Lagos.

Campbell and his fellow musicians established themselves against the odds. Both he and Hughes continued to work with Caribbean musicians, among them such notables as trumpeter Shake Keane and saxophonist George Tyndale. Campbell used white musicians as well: Denis Preston recorded him for Columbia in 1966 with a very mixed personnel.

What Campbell, Hughes and the West African Rhythm Brothers did was to create a new African music influenced by their experience as migrants — and in Campbell's

own case with the deliberate inclusion of elements first encountered on the beach in Lagos.

In 1972, Ambrose Campbell did a disappearing act. He moved to Los Angeles with record producer Denny Cordell — the two of them to go into business with Leon Russell, from Oklahoma. Whilst a new studio was completed, Campbell joined Russell on the road, bringing his percussion skills to 'blue-eyed soul' without missing a beat. (He says now that his ease with such American music can be traced back to his early exposure to Western ideas. Country idioms were not unknown to West Africans, amongst whom Jim Reeves was to become a perennial favourite.) He recorded as a percussionist, too — most notably on Russell's million-selling collaboration with Willie Nelson, One For The Road.

Nearly all the tracks assembled here come from recordings made for the Melodisc label and originally released as 10-inch 78rpm singles. People who bought these records at the time can still recall how it was when the percussion team — among them Ade Bashorun, Salustiano Dos Anjos, Manny Myers and 'Lati' Pedro — built their polyrhythms in Ola Dosunmu's kingdom. With the melodic guitars of Brewster and Ambrose coming together behind Campbell's soothing voice, the musicians contrived to paint an evocative, enduring picture of palmwine Lagos nights.

For English people, emerging from the shadow of wartime deprivation, this fresh 'sunshine' music was just what the doctor ordered. The atmosphere at the clubs, and the warmth of their African clientele, contrasted favourably with the restraint and stiff upper-lip which might have got the country through the war, but which — for some people — left something missing.

This music and the startling taste of hot West African food were for many white people the keys to learning about a new way of being. The Nigerians had an equivalent experience. Often the hard way, they were learning about a new society and how best to conduct themselves in it. For years the communities came together and partied, often in humble surroundings, but with a determination to fight prejudice and cross boundaries that has endured to this day. Such exchange and interaction have helped to make British society what it is now, warts and all. And music was at the heart of the process.

Val Wilmer

Share Article

Details

Genre

Release Date

15.04.2013

Cat No

HJRLP 21